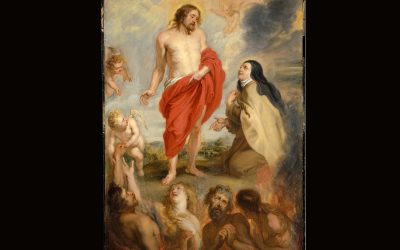

Image: St. Bernard of Clairvaux Receiving the Last Rites, Wolfgang Sauber,

sourced from Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

By Amber Kinloch

Anointing of the Sick—formerly known as Extreme Unction—is, perhaps, the most unfamiliar sacrament. Many have never been present at an anointing and don’t know what to expect. Some might find the idea of being anointed strange, uncomfortable, or just unnecessary.

This is unfortunate. All of us, at some point or another, will likely find ourselves in a position to help someone receive this sacrament. Or else we’ll stand in need of it ourselves. We should be suitably prepared beforehand so that we are ready when the time comes.

What are the basic things everyone should know about this sacrament? Let’s take a look.

Why Do We Have This Sacrament?

Anointing of the Sick has its roots in Christ’s own example of healing the sick as a sign of the coming of God’s Kingdom. Illness itself is a consequence of Original Sin and part of our fallen state. “In illness, man experiences his powerlessness, his limitations, and his finitude. Every illness can make us glimpse death” (CCC 1500).

The Catechism continues: “Illness can lead to anguish, self-absorption, sometimes even despair and revolt against God. It can also make a person more mature, helping him discern in his life what is not essential so that he can turn toward that which is. Very often illness provokes a search for God and a return to him” (CCC 1501).

For her members who are afflicted with serious physical suffering, the Church offers this sacrament in order to strengthen them and help them press on their way towards Heaven. According to the Catechism, the specific graces of this sacrament include:

“the uniting of the sick person to the passion of Christ, for his own good and that of the whole Church;

“the strengthening, peace, and courage to endure in a Christian manner the sufferings of illness or old age;

“the forgiveness of sins, if the sick person was not able to obtain it through the sacrament of Penance;

“the restoration of health, if it is conducive to the salvation of his soul;

“the preparation for passing over to eternal life.”

—CCC 1532

Who Administers This Sacrament and Who Can Receive It?

A priest or bishop is the minister of this sacrament. A deacon cannot administer it.

There is some ambiguity regarding who can be anointed. The Catechism says that “[this] is not a sacrament for those only who are at the point of death. Hence, as soon as anyone of the faithful begins to be in danger of death from sickness or old age, the fitting time for him to receive this sacrament has certainly already arrived” (CCC 1514).

I spoke with an experienced priest about whom he would anoint and why. Fr. J. explained that danger of death might include those advanced in years who might simply die of old age, a sudden heart attack, or a stroke. Likewise, those undergoing serious operations qualify—for instance, a patient having heart or lung surgery. Less serious surgeries, e.g., a knee surgery, typically would not qualify unless there is some other significant threat posed to one’s life. For example, those with hemophilia would be at risk owing to their body’s poor ability to clot blood.

But what if someone’s not in clear danger of death? Can they be anointed? What’s the criteria?

Here Fr. J. mentioned how illness wears a person down. To be clear, we are not talking about the flu here. The flu might lay you flat on your back, but you’ll likely feel a whole lot better in a few days. What’s meant here are long-standing chronic illnesses that hold you in their grip for years with no end in sight. In this case, a person (even a younger individual) might be anointed in order to strengthen them under the weight of the heavy cross they shoulder.

I also asked Fr. J. about people he would not anoint. Two groups of significance include children under the age of seven and those severely mentally disabled from birth. This is because these people are seen by the Church as being incapable of committing sin. They retain their Baptismal innocence and do not need forgiveness of sin. Likewise, they do not have the capacity, as it were, to interiorly suffer and be tempted in the same way others do.

Another note: This sacrament is intended for those in the state of grace. Those who are conscious and able to communicate, who have committed mortal sin(s), and who have not been to Confession should not receive this sacrament. That said, if a person has committed a mortal sin and is unconscious, this sacrament may be administered. God, in His Mercy, can forgive that person through this sacrament provided they are rightly disposed in the depths of their soul.*

*This does not mean someone should wait to reach this state, of course. Purposefully trying to avoid going to Confession when you know you need it clearly indicates a lack of contrition.

How Often Can We Receive This Sacrament?

Fr. J. said that with regard to those who are elderly, he might administer this sacrament to them once or twice a year. Likewise, those dealing with a serious illness (e.g., brain cancer) may be anointed.

This sacrament may be received multiple times if a person previously anointed recovers and falls sick again or shows a significant decline in health (CCC 1515).

When in doubt, call a priest. It is better for you to call and for Father to say, “No, I don’t think it’s time,” then for you to put off calling and possibly deprive yourself or another of this rich source of grace.

What Happens during the Rite of Anointing?

There are many variations regarding how the rite of anointing is done depending on the circumstances. Anointings may be done during Mass or—more often, probably—outside of Mass. Ideally, like during a serious illness, we will be able to call the priest well in advance. In the case of an emergency, though, an anointing might take place in as little as thirty seconds.

Let’s assume, though, that a full, simple form of the rite of anointing will take place. What happens when the priest arrives in your home or the hospital room?

First, there is the Sign of the Cross, a greeting, and an opening prayer. Next, if the sick person wishes, the priest can hear their Confession while everyone else clears out of the room. After this, the priest prays and anoints the person’s forehead and palms with blessed oil before the closing prayer. He might also give the person Holy Communion afterwards if they’re capable of receiving the Eucharist.

If the person is on the point of death (like Father might come back and not find them alive), the Apostolic Pardon may be given. Fr. J. described the Apostolic Pardon as a “Get Out of Purgatory” card. Put another way, Confession and Anointing of the Sick are both sacraments that forgive sins. The Apostolic Pardon—a special plenary indulgence for the dying—forgives all the temporal punishment due to sin, provided the person is properly disposed.

How Can We Prepare Ourselves for an Anointing?

I mentioned to Fr. J. that I’ve read that people frequently decline the opportunity to receive this sacrament. He confirmed that this often happens. Priests go into the hospital rooms of the ill and dying and are turned away. Patients and their families would rather watch TV.

Prepare yourself for death. Do not bet on your salvation. The choices you make every day form and mold you. If you neglect to strive for sainthood now, you might fall into Hell later due to sheer indifference.

When you’re waiting for the priest to come for an anointing, here’s how you can prepare:

- Let people, including medical staff, know that Father is coming.

- Turn off the TV and put away cell phones. Pray or sit in silence. Prepare your heart.

- If applicable, tidy up the sick room out of respect for the priest.

- Show respect for Father when he comes. If he’s bringing the Eucharist, avoid idle talk out of respect for Our Lord.

- Partake in the rite of anointing by making responses, kneeling and standing as appropriate, etc., if you are able.

This sacrament of Anointing of the Sick is a precious gift. Take advantage of it and prepare yourself and others well. Most of all, do not take salvation for granted. It is a gift. God offers it, but He will not force us to accept it. Lay hold of it now and strive every day for holiness that you might end your life safe in His embrace.

Amber Kinloch

Amber writes from the bunker of her living room. There she hunkers down with her laptop and a blanket while keeping an eye and ear tuned in to the activity of family life. Music set on loop keeps her energy flowing as she muses on the deeper happenings of ordinary life and what food to restock the fridge with.

Thank you, Amber. A great reminder. A beautiful, calming sacrament at a stressful time. Even for the observers.

Just one simple correction: in the last paragraph, line 5. “God will not force . . . “

Thank you, Margaret. “A beautiful, calming sacrament” sums it up perfectly.

Correction made. Thank you for pointing this out.