By Rose Leigh

The purpose of sacred art is to lift your thoughts toward God. If you’re a visual person, art can be a helpful and enjoyable way to draw yourself into prayer.

When you’re in front of a piece of sacred art, don’t just glance at it for a few moments and move on. Instead, sit with the image for a while, taking everything in and employing your imagination, and let that lead you into prayer. A bit of knowledge about the artistic period or style helps in interpreting the artwork, too.

I’ve chosen three great works of sacred art for us to look at today. I invite you to pray with them as we examine what’s happening in each one. I hope this inspires you to search for more sacred art and do the same thing.

The Renaissance

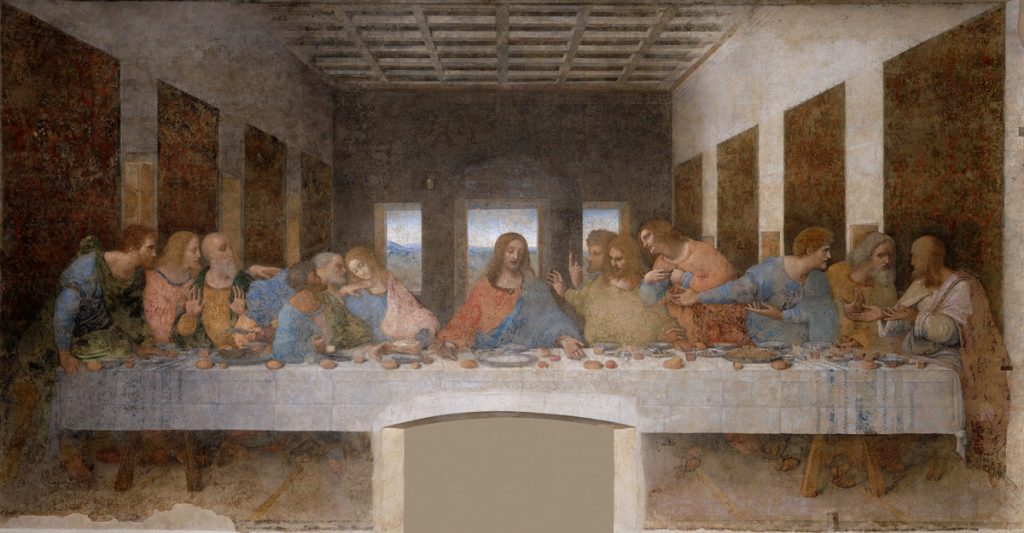

Let’s start with something familiar: Leonardo da Vinci’s famous painting The Last Supper, 1495–98 AD. It’s a fresco; da Vinci painted this directly onto the plaster in the dining room of a convent. Imagine eating dinner and looking up to see this:

The composition is, in typical Renaissance fashion, carefully planned out in one-point linear perspective. If you trace all the edges of the room with a ruler, they converge on Jesus, who sits with a calm, contemplative sadness.

However, the apostles are anything but calm. Jesus has just announced that, “Amen, amen, I say to you, one of you will betray me” (see John 13:21–30 and the other gospels). The apostles’ body language expresses shock, disbelief, denial, and confusion; a few are protesting to Jesus, “Surely it is not I, Lord?” (Matthew 26:22). Judas (in the fifth seat from the left) holds a money bag and reaches forward to fulfill Jesus’ prediction that his betrayer will be “the one to whom I hand the morsel after I have dipped it” (John 13:26).

Imagine yourself inside this scene. What was it like to hear Jesus say that someone in the room—someone the apostles knew and had traveled with—would betray Him? The apostles were fallible, just like we are today. They would flee from Jesus in the garden of Gethsemane just a few hours after the moment in this painting. Even at the Last Supper, they didn’t fully understand what Jesus had been teaching them and what He had foretold about His own death. Would the things Jesus was saying have been too unthinkable for you to accept or understand, in this moment?

For more commentary on this painting, see Brad Miner’s article from The Catholic Thing.

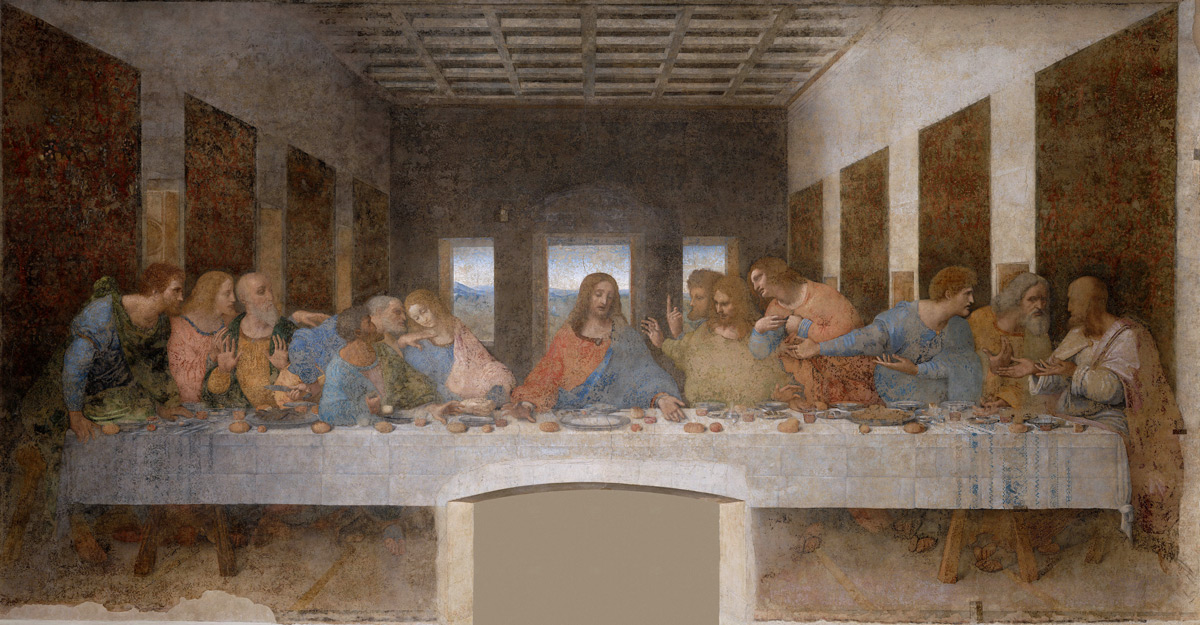

Icons

Now let’s look at something completely different: a Russian Orthodox icon by Andrei Rublev, Trinity (or Troitsa), c. 1400–10 AD. In contrast to Western art, this icon reflects the Russian Orthodox Church’s hesitancy about depicting God the Father and God the Holy Spirit in art. Jesus had a physical body, but how can the traditional images of an old man and a dove really represent the Father and the Holy Spirit, respectively?

So for inspiration, Rublev turned to Genesis 18:1–15, in which “three men” visit Abraham and tell him that his wife Sarah will have a child. These “men” are the Lord:

On Catholic Link, Garrett Johnson explains, “When speaking of icons, in reality, one doesn’t say that he or she has ‘painted’ an icon. They are ‘written’ and ‘read’, going from left to right.” Rublev’s icon explains the theological mystery of the Trinity through symbolic imagery. The three men from Genesis are portrayed as three identical angels, none of whom is larger or more important than another (we believe in one God)—but yet they are all distinct persons (there are three Persons in the Trinity). The angels sit at a table, blessing a calf in a chalice on the altar-like table. This calls to mind the Eucharistic sacrifice.

The three angels all wear blue, which signifies divinity, but each one also wears another color, and there is a symbol in the background behind each. Multiple meanings may apply, but here is one way to read the icon: The Father on the left wears a red or purple robe to signify royalty. Behind Him, Abraham’s house references the passage that, “in my Father’s house are many dwelling places” (John 14:2). In the middle, the Son wears red, reminding us of His humanity, and the tree in the background reminds us of the Cross. On the right, the Holy Spirit wears pale green, as the Giver of Life. The rock behind Him references Moses drawing life-giving water from the rock (Exodus 17:1–7).

Icons may look strange if you’re used to Western art, but looking at the symbolism should serve as a starting point for meditating on this icon and the mystery of the Trinity.

For more about the symbolism in this icon, see these articles from EWTN, Aleteia, and Transfiguration of Our Lord Russan Orthodox Church.

Baroque

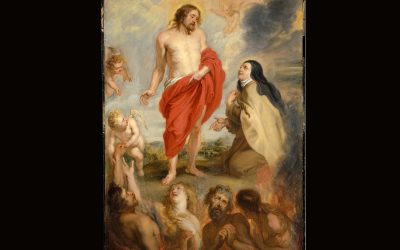

We’ll end with Caravaggio’s The Calling of St. Matthew (1599–1600 AD).

Baroque art holds a special place in Catholic history. After the Reformation, the Church wished to re-instill an understanding of the Faith in a population that had been influenced by Protestant ideas. Baroque art is dramatic, dynamic, and emotional, appealing to the senses in order to communicate truths about the Faith.

This painting by Caravaggio captures the moment when Jesus calls Matthew the tax collector to be one of his disciples (Matthew 9:9–13). In Jewish cities at that time, tax collectors were hated, because they worked with the Roman occupiers to tax their fellow Jews. It was not considered a worthy occupation, but it made one wealthy.

In this scene, a bearded Matthew sits at the table with several finely dressed friends, two of whom are so absorbed in counting their money that they don’t even notice Jesus coming in. On the right, Jesus points at Matthew in invitation, just as God offers a life-giving hand to Adam in Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel.

But Matthew, in typical human fashion, is hesitant to leave his nice life with all his riches and friends. “Me, really?” Matthew’s body language seems to say. Don’t we all have moments like that? Other people will go become a saint, but not me. Someone else will step up and perform that ministry. I’m too sinful to do big things for God. Luckily for Matthew, there’s a ray of light and grace falling on him, and the rest is history.

Elizabeth Lev’s book How Catholic Art Saved the Faith: The Triumph of Beauty and Truth in Counter-Reformation Art examines Baroque artwork in more detail.

Rose Leigh

Rose has been drawing and writing since she could hold a pencil, creating worlds of giants, fairies, and adventurers from her imagination. She works as a graphic designer and loves discussing the good and creative aspects of literature, art, and film.

0 Comments